The Back Parlor Gallery was created in 2008 to feature annual exhibits that are produced in-house on subjects relative to the historic site’s mission, providing the opportunity to exhibit items from the collection not normally on display. The Back Parlor Gallery is closed for the installation of the fire suppression system in Bedford House. All our exhibits are available digitally HERE

These are a few of my Favorite Things

Staff, volunteers, Friends members and interns were asked to select their favorite collections objects to share with you.

Staff, volunteers, Friends members and interns were asked to select their favorite collections objects to share with you.

History Myth-Understood

Historic myths are told daily at house museums and historic sites all over the country. These myths have become so common that they are often viewed as fact. How many of these have you heard?

Historic myths are told daily at house museums and historic sites all over the country. These myths have become so common that they are often viewed as fact. How many of these have you heard?

Men would break off the stem of a clay pipe to not spread germs when sharing it.

George Washington’s teeth were made of wood.

The Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776.

Hidden messages sewn into quilts provided runaway slaves directions along the Underground Railroad.

Artists charged more to paint hands, as they are more difficult to execute accurately.

Come learn the truths behind these common myths.

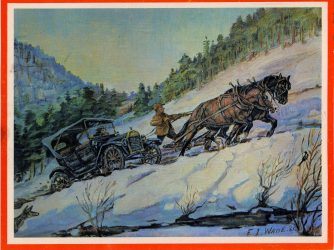

The Holiday Season at John Jay’s Bedford House

During John Jay’s time, in the early 19th century, Christmas was a solemn, religious holiday, celebrated with church, prayer and bible readings. But the Jays and their contemporaries did celebrate the season beginning with Thanksgiving to celebrate the harvest, through Twelfth Night (January 6th) to celebrate the Epiphany. This exhibit includes family Christmas cards, ornaments, historic photos along with winter costumes and accessories.

During John Jay’s time, in the early 19th century, Christmas was a solemn, religious holiday, celebrated with church, prayer and bible readings. But the Jays and their contemporaries did celebrate the season beginning with Thanksgiving to celebrate the harvest, through Twelfth Night (January 6th) to celebrate the Epiphany. This exhibit includes family Christmas cards, ornaments, historic photos along with winter costumes and accessories.

.

Moments in Time: Photographs from the Jay Family Collection

Photographs have a capacity to connect us with people and places long gone, perhaps better than any other pictorial medium except film. Life is captured in an instant: a moment of joy, or wonder, or wistful reflection. The Jay-Iselin family, who lived at John Jay Homestead, compiled an extensive collection of family photographs over many decades, from early daguerreotypes to modern snapshots. Moments in Time will include photographs stretching from the 1850s to the 1950s, depicting the family’s growth, its travels, and its participation in daily life and special occasions.

Photographs have a capacity to connect us with people and places long gone, perhaps better than any other pictorial medium except film. Life is captured in an instant: a moment of joy, or wonder, or wistful reflection. The Jay-Iselin family, who lived at John Jay Homestead, compiled an extensive collection of family photographs over many decades, from early daguerreotypes to modern snapshots. Moments in Time will include photographs stretching from the 1850s to the 1950s, depicting the family’s growth, its travels, and its participation in daily life and special occasions.

Reflections on our Past: A Viewer Response Exhibit

The period rooms in John Jay’s house are installed in the style of the 1820s, the last ten years of the Founding Father’s life. Jay moved to Katonah after retiring from politics in 1801, and lived in the house until his death in 1829. His descendants continued to live here as late as the 1950s.

The period rooms in John Jay’s house are installed in the style of the 1820s, the last ten years of the Founding Father’s life. Jay moved to Katonah after retiring from politics in 1801, and lived in the house until his death in 1829. His descendants continued to live here as late as the 1950s.

The museum’s historic collection covers 150 years of Jay family occupation, but objects that date after John Jay’s death are kept in storage. A varied selection of seldom exhibited objects, both items that belonged to the Jay family and objects that were later donated by local benefactors, were assembled for the Reflections exhibit. The fifty objects selected included a Civil War sword, a 1930s lady’s tweed riding coat, a document signed by John Jay in the 1790s, a Victorian sausage stuffer, portraits, antique furniture, old silver, and a Chinese birdcage.

An equally wide spectrum of people from John Jay Homestead’s community, from eminent scholars to local children, from public officials to friends and neighbors, each selected on object to comment on in whatever medium they wish.

Am I Not Myself a Woman? The First Generations of Jay Women at Bedford

This exhibit focused on women’s lives in the late 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, as exemplified by John Jay’s wife, Sarah Livingston Jay, her three daughters, Maria, Ann, and Sarah Louisa, and her daughter-in-law, Augusta McVickar Jay. The exhibition examined the roles and responsibilities women had to fulfill during these years, as well as their opportunities for personal growth through education and religious observance.

This exhibit focused on women’s lives in the late 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, as exemplified by John Jay’s wife, Sarah Livingston Jay, her three daughters, Maria, Ann, and Sarah Louisa, and her daughter-in-law, Augusta McVickar Jay. The exhibition examined the roles and responsibilities women had to fulfill during these years, as well as their opportunities for personal growth through education and religious observance.

Artifacts from John Jay Homestead’s historic collection were displayed, including painted and sculpted portraits of the Jay women, an elegant pair of mahogany sewing tables believed to have been purchased for Maria and Ann Jay, family jewelry, Maria Jay’s book of pressed flowers, and Sarah Jay’s grandmother’s early 18th-century silver teapot, which was passed down through generations of women in the family.

Slaves, Slavery, and the Jay Family

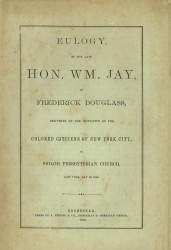

The Slaves, Slavery, and the Jay Family exhibit spanned the years from John Jay’s grandfather’s probable involvement in the slave trade in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, continued through the period of John Jay’s father’s and his own slave ownership, and concluded with the abolitionist activity of John Jay’s sons, Peter Augustus and William, and his grandson, John Jay II. John Jay’s own actions in regard to slavery were examined: while publicly advocating an end to it as a president of the New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and signing, as governor, the first law that began the process of slowly ending slavery in New York State, he continued to own, purchase, rent, and sell slaves, believing that the practice needed to be ended gradually.

The Slaves, Slavery, and the Jay Family exhibit spanned the years from John Jay’s grandfather’s probable involvement in the slave trade in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, continued through the period of John Jay’s father’s and his own slave ownership, and concluded with the abolitionist activity of John Jay’s sons, Peter Augustus and William, and his grandson, John Jay II. John Jay’s own actions in regard to slavery were examined: while publicly advocating an end to it as a president of the New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and signing, as governor, the first law that began the process of slowly ending slavery in New York State, he continued to own, purchase, rent, and sell slaves, believing that the practice needed to be ended gradually.

Also told were stories of slaves owned by the Jays, illustrating their experiences: Abby’s becoming a fugitive, Ben’s working to earn his freedom, Clarinda’s having to live apart from her spouse because he was owned by a different slave-owner, Caesar’s being rented out as a sailor. The abolitionist activities of John Jay’s son William and his grandson John were illustrated with rare documents from John Jay Homestead’s historic collection, revealing their collaboration with such important advocates for African-American freedom as the publisher David Ruggles and the Underground Railroad’s Stephen Myers.

From Oppression to Freedom: John Jay and His Huguenot Heritage

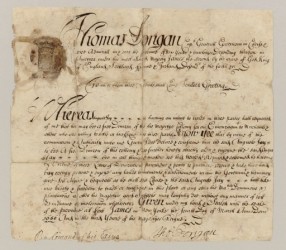

From Oppression to Freedom explored the religious persecution the Jays suffered as Protestants in France during the 17th century, their flight as refugees, and John Jay’s grandfather’s arrival in North America in the 1680s, founding the American branch of the family. John Jay’s religious and political convictions were examined in the light of his family’s experience. Finally, the impact that the persecution of religious minorities had on Americans was covered, as was how this inspired the freedom of religion and the separation of Church and State now enshrined in the United States Constitution.

From Oppression to Freedom explored the religious persecution the Jays suffered as Protestants in France during the 17th century, their flight as refugees, and John Jay’s grandfather’s arrival in North America in the 1680s, founding the American branch of the family. John Jay’s religious and political convictions were examined in the light of his family’s experience. Finally, the impact that the persecution of religious minorities had on Americans was covered, as was how this inspired the freedom of religion and the separation of Church and State now enshrined in the United States Constitution.

The exhibition included what is believed to be the oldest surviving Jay family document of American origin: the 1686 letter of denization that allowed Auguste Jay, John Jay’s grandfather, to live and conduct business in the English colony of New York. Also on view was an oil portrait of Auguste, his son’s (John Jay’s father’s) silver seal, and the family’s 1724 oversized copy of The Book of Common Prayer.

John Jay and the Treaty of Paris

John Jay played a major role in formulating the treaty that marked the formal end of the Revolutionary War, bringing with it world recognition of America’s independence. The Treaty of Paris, as this treaty came to be called, established borders west to the Mississippi, thus doubling the size of the new republic and giving it vital commercial and trade advantages.

John Jay played a major role in formulating the treaty that marked the formal end of the Revolutionary War, bringing with it world recognition of America’s independence. The Treaty of Paris, as this treaty came to be called, established borders west to the Mississippi, thus doubling the size of the new republic and giving it vital commercial and trade advantages.

This exhibit, commemorating the 225th anniversary of the Treaty of Paris included the Jay family’s copy of the Benjamin West portrait of the American Peace Commissioners; a coat and embroidered vest that Jay wore when introduced by Benjamin Franklin to the French foreign minister; and a copy of Jay’s Red Line Map, which was used in settling the boundaries of the United States.